Scaffolding Science Achievement in a Culturally Diverse Classroom: Bridging the Gap with Virtual Peers

Overview

In this project, we aim to address the systematically-reduced standardized test scores of African American students compared to their Euro-American peers by using virtual peer technology to understand the role of dialect, and more broadly, cultural congruence, on students’ performance, and to help students achieve in the classroom. Our results show that African American children demonstrate awareness of how to use different language styles in different situations (such as using more African American Vernacular English during collaborative play than they use when practicing a formal presentation by role-playing as a teacher and student), and that they make this language transition whether they are collaborating with a human peer or a virtual peer partner [Cassell et al., 2009]. Additionally, we have shown that African American children demonstrate improved verbal science reasoning after hearing an example of this type of reasoning from a virtual partner who spoke using the vernacular dialect than one who provided the same content in the standard dialect [Finkelstein et al., 2013]. This work also demonstrated that children are more fluent when speaking socially with a virtual partner which first introduces itself in the vernacular dialect than one which introduces itself with a standard English dialect. Regardless of partner, children also demonstrate increased fluency when they are speaking in the vernacular dialect rather than the standard dialect themselves [Finkelstein et al., 2012]. Our current and future work builds on these results by building language and code-switching models of African American Vernacular English into our system, creating content for more educational domains into our virtual peer system, investigating the mechanisms behind improved performance with same-dialect virtual partners, and exploring the ethical considerations around developing culturally-sensitive classroom systems.

Our motivations

The achievement gap, the systematic lower reading, science, and math test scores among African American students compared to their Euro-American peers, is a systematic problem in our education system – especially for children who do not use the Mainstream American English literacy practices expected in most American classrooms. especially for children who do not use the Mainstream American English literacy practices expected in most American classrooms. In particular, with increasing frequency, students’ non-standard dialects have been identified as being strongly associated with reduced performance on mainstream evaluations of literacy. These findings, along with countless qualitative observations of non-standard dialect within the classroom, have motivated extensive and controversial discussions among teachers, administrators, and researchers alike:

How do we support students in developing and maintaining their cultural identity?

How do we do it while still acknowledging the reality of there being a code of power which is often used as an index of achievement and success in contemporary American society?

How do we do it in such a way that allows us to illuminate the mechanisms behind the relationship between dialect and learning in the elementary school classroom, including the effect of the commonly-held misconceptions about the nature of non-standard dialects?

In particular, our work right now focuses on African American Vernacular English; however, the methodologies and principles we employ can be applied to other cultural or regional non-standard dialects (e.g., Hispanic English or Pittsburghese), and future goals of this project aim to expand our focus.

Our methodologies

In our work, we examine the linguistic practices of particular communities – both inside and outside school – to understand how language is used within a community. This involves:

- Extensive classroom observation of local schools that vary in socio-economic status, ethnic diversity, and standardized test performance

- Leading informal collaborative learning sessions at local community centers and afterschool programs

- Interviews and co-design sessions with students, parents, teachers, and administrators

These observations, discussions, and design sessions are subsequently analyzed to help us respond to a number of fundamental questions. For example, what is the range of verbal and non-verbal behaviors different students may display when interacting with human peers, such that we design technologies who display realistic, engaging, and culturally-appropriate behaviors? How can we integrate students’ perceptions of culture, as well as their own ideas on how to improve on the design of our technology, into our iterative design process?

Based on the outcomes of these observations, discussions, and design sessions, we build virtual peers as a way to support students as learning partners in the classroom, educate teachers and administrators about cultural differences, and better understand the role of culture and language within a classroom. To do this, we examine the effect of virtual peers that are able to demonstrate cultural alignment with different ethnic groups along physical, verbal, and non-verbal dimensions. To do so, we manipulate the physical, verbal, and non-verbal behaviors of virtual peers who can engage with students in both social and formal and informal learning tasks, and examine how different instantiations of agents affect students’ collaborative talk, learning gains, and self-efficacy

What we've found (so far!)

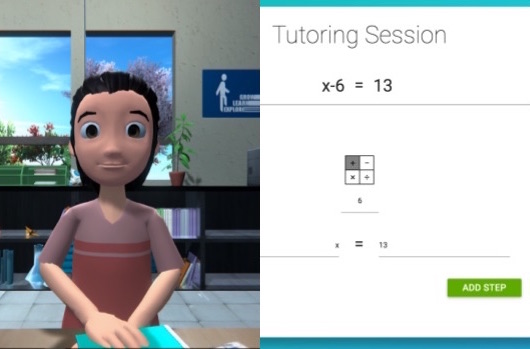

Our current system for exploring these questions of dialect and learning is Alex, a virtual peer who engages children in the science activities of the third grade classroom, interspersed with the getting-to-know-you activities that all children engage in both inside and outside school. While the physical appearance of Alex is designed to be ethnicity and gender ambiguous, the verbal and nonverbal discourse behaviors are based upon human models of African American children between the ages of 8 – 10 years old.

Our results show that African American children demonstrate awareness of how to use different language styles in different situations (such as using more African American Vernacular English during collaborative play than they use when practicing a formal presentation by role-playing as a teacher and student), and that they make this language transition whether they are collaborating with a human peer or a virtual peer partner [Cassell et al., 2009]. Additionally, we have shown that African American children demonstrate improved verbal science reasoning after hearing an example of this type of reasoning from a virtual partner who spoke using the vernacular dialect than one who provided the same content in the standard dialect [Finkelstein et. al, 2013]. This work also demonstrated that children are more fluent when speaking socially with a virtual partner which first introduces itself in the vernacular dialect than one which introduces itself with a standard English dialect. Regardless of partner, children also demonstrate increased fluency when they are speaking in the vernacular dialect rather than the standard dialect themselves [Finkelstein et al., 2012]. These results call for a re-examination of the cultural assumptions followed in the design of educational technologies, with a specific emphasis on the way in which we index culture and identity, and the ways in which we ask culturally-underrepresented groups to participate in learning activities.

What we're working towards now

Our results thus far have demonstrated the educational benefit for children working with a same-dialect virtual peer on a science task [Finkelstein et al., 2013], though the mechanisms behind this benefit are still unclear. For example, our participants (all African American AAVE-speaking students) may have performed best with the same-dialect virtual peer because they were more easily able to process information provided in their native dialect, thus reducing the cognitive load of the task; conversely, students may have performed best with the same-dialect virtual peer because they felt increased rapport with the agent who displayed similar linguistic tendencies to their own. In order to evaluate these two competing hypotheses, we are exploring how children from different ethnic backgrounds respond to virtual agents that either appear Euro-American or African American, and either speak in Mainstream American English or African American English.Additionally, our work relies on our virtual agents displaying verbal and non-verbal behaviors that are realistic representations of the target cultural groups with which we are working. As such, our lab is continuing to work on studying groups of children in different communities to understand the range of behaviors that are expressed in different situations. For example, we are working towards developing a language model of African American Vernacular English that demonstrates the relationship between feature usage across different domains, within different social contexts, and to different interlocutors. We are also carrying out this process with non-verbal behaviors, creating models of the gestures, gaze patterns, and body movements used by different populations of students across a variety of situations.